1 Newton’s law of gravitation

Newton formulated that the gravitational force between two point masses is directly proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them (which is known as the inverse square law).

\[ |\vec{F}| \propto \frac{m_1 m_2}{r^2} \tag{1.1}\]

Where: \(\vec{F}\) is the force acting on one of the bodies from the other, \(m_1, m_2\) are the masses of the bodies and \(\vec r\) is the vector from mass \(m_1\) to \(m_2\) whose magnitude is \(r\).

While the equation is enough to know to contemplate rest of the Keplerian model of orbital mechanics, one might be curious as to how did Newton arrive at this formulation. We answer that in the following sections taking the case of planetary orbits around the Sun.

1.1 Kepler’s Laws of planetary motion

Kepler, building on Tycho Brahe’s detailed astronomical data, established these laws:

1st Law: Planets move in elliptical orbits with the Sun at one focus.

2nd Law: The line joining a planet and the Sun sweeps out equal areas in equal time.

3rd Law: The square of a planet’s orbital period is proportional to the cube of its semi-major axis.

\[ T^2\propto a^3 \tag{1.2}\]

Where \(T\) is the time period and \(a\) is the semi-major axis.

Now we will see how each of the above laws helped Newton come to his conclusion.

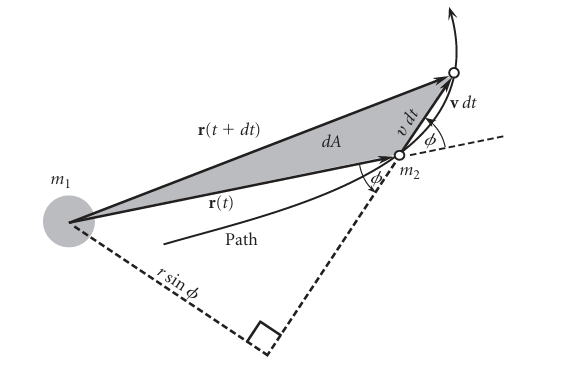

1.2 Area Law implying central force

Newton inferred that the force must be a central force—pointing toward the Sun—because Kepler’s Second Law (the area law) states that a planet sweeps out equal areas in equal time. The following derivation will make it clear as to how.

We know,

\[ \frac{dA}{dt}=K \]

where \(K\) is a constant.

Here \(m_1\) is the Sun and \(m_2\) is the planet.

Using the formula for area of triangle on the infinitesimal area dA, we get

\[ dA=\frac{1}{2}\times vdt\times r\sin{\phi} \]

\[ \Rightarrow dA=\frac{1}{2} r(v \sin{\phi}) dt= \frac{1}{2} rv_{\perp} dt \]

We know that \(\vec{h}=rv_{\perp} \hat{h}\) , where \(\vec{h}\) is the specific relative angular momentum of \(m_2\) wrt \(m_1\).

Angular momentum is defined as: \[ \vec{H}=\vec{r}\times (m\vec{v}) \] \[ \vec{h}=\vec{r}\times \vec{v}=rv\sin{\phi} \hat{h} \] where \(\phi\) is the angle between the position vector \(\vec{r}\) and the velocity vector \(\vec{v}\), and \(\hat{h}=\hat{r}\times \hat{v}\) is the unit vector perpendicular to the plane of motion.

\[ \boxed{\frac{dA}{dt}=\frac{h}{2}=K} \tag{1.3}\]

The angular momentum of \(m_2\) wrt \(m_1\) turns out to be a constant. This only happens if the torque about the Sun is zero, which in turn implies that the force has no component perpendicular to the radius vector. Therefore, the force must always point along the line joining the planet and the Sun, making it a central force.

1.3 Derivation of the inverse-square relationship

We now work in polar coordinates for ease of derivation. For a particle moving under a central force:

\[ \vec{F} =m\vec a= m(\ddot{r} - r \dot{\theta}^2) \hat{r} + m(r \ddot{\theta} + 2\dot{r}\dot{\theta}) \hat{\theta}\qquad\text{(Newton's 2nd law)} \]

\[ \frac{d\hat r}{dt}=\dot\theta\,\hat\theta,\qquad \frac{d\hat\theta}{dt}=-\dot\theta\,\hat r, \tag{1.4}\] following directly from differentiating the explicit Cartesian definitions of the unit vectors: \[ \hat r = \cos\theta\,\hat\imath + \sin\theta\,\hat\jmath,\qquad \hat\theta = -\sin\theta\,\hat\imath + \cos\theta\,\hat\jmath. \]

Using Equation 1.4, we can compute \(\ddot{\vec r}\) doing the following: \[ \vec v=\dot{\vec r}=\frac{d}{dt} (r\hat r) \]

Which gives,

\[ \vec v= \dot r\hat r+r\dot{\theta}\hat \theta \tag{1.5}\]

And, \[ \vec a=\dot{\vec v} \]

gives the above formulation of acceleration

The \(\hat{\theta}\)-component is zero (since force is radial) such that angular momentum is conserved.

The radial equation simplifies to:

\[ m\left( \ddot{r} - r \dot{\theta}^2 \right) = F(r) \tag{1.6}\]

Now, from Kepler’s first law, we see that the orbit must be an ellipse with the Sun at one focus. Hence, the equation

\[ r(\theta)=\frac{p}{1+e\cos{\theta}} \tag{1.7}\]

holds. Here \(p\) is the semi latus-rectum, \(e\) is the eccentricity of the ellipse orbit and \(\theta\) is the angle between the line joining the focus to the point and line joining focus to the periapsis.

We get a new variable \(u\) where:

\[ u=\frac{1}{r} \]

Then,

\[ \frac{dr}{d\theta}=-\frac{1}{u^2}\frac{du}{d\theta} \]

We know that specific angular momentum \((\vec h)\) is

\[ \vec h= \vec r \times \vec v \]

From \(\vec r=r\hat r\) and \(\vec v= \dot r\hat r+r\dot{\theta}\hat \theta\):

\[ \vec h= \vec r \times \vec v = r\hat r \times \left(\dot r\hat r+r\dot{\theta}\hat \theta\right) = r^2\dot{\theta}\hat h \]

Where \(\hat h = \hat r \times \hat \theta\) is the unit vector perpendicular to the plane of motion. Implying,

\[ h=r^2\dot \theta \]

\[ \dot r=\frac{dr}{dt}=\frac{dr}{d\theta}\frac{d\theta}{dt}=-\frac{1}{u^2}\frac{du}{d\theta}hu^2 \]

\[ \boxed{\dot r=-h\frac{du}{d\theta}} \]

Differentiating the above wrt \(t\):

\[ \ddot r=-h\frac{d}{dt}\left(\frac{du}{d\theta}\right)=-h\dot \theta\frac{d^2u}{d\theta^2} \]

Again we substitute \(\dot \theta=hu^2\) onto the above equation.

\[ \ddot r=-h^2u^2\frac{d^2u}{d\theta^2} \tag{1.8}\]

Substituting Equation 1.8 and \(\dot \theta=hu^2\) onto Equation 1.6 :

\[ -h^2 u^2 \frac{d^2 u}{d\theta^2} - \frac{1}{u} \cdot h^2 u^4 = \frac{F(r)}{m} \] Simplify: \[ -h^2 u^2 \frac{d^2 u}{d\theta^2} - h^2 u^3 = \frac{F(1/u)}{m} \]

Multiply both sides by \(-\frac{1}{h^2 u^2}\):

\[ \frac{d^2 u}{d\theta^2} + u = -\frac{F(1/u)}{m h^2 u^2} \tag{1.9}\]

Now, substituting \(u=\frac{1}{r}\) onto Equation 1.7 gives:

\[ u=\frac{1}{p}+\frac{e}{p} \cos{\theta} \]

\[ \Rightarrow \frac{du}{d\theta}=-\frac{e}{p}\sin \theta\quad\text{and}\quad\frac{d^2u}{d\theta^2}=-\frac{e}{p}\cos \theta \]

Using the above on Equation 1.9 we get:

\[ \frac{1}{p}+\frac{e}{p} \cos{\theta}-\frac{e}{p} \cos{\theta}=-\frac{F(1/u)}{m h^2 u^2} \]

And putting back \(u=\frac{1}{r}\),

\[ \vec F(r)=-\frac{mh^2}{pr^2} \]

\[ \Rightarrow \vec F \propto \frac{1}{r^2} \]

This showed Newton that the acceleration required to keep a planet in orbit must follow an inverse-square law.

To test the universality of this law, Newton compared the gravitational acceleration near Earth’s surface ( \(a_E\approx 9.81 m/s^2\)) with the centripetal acceleration needed to keep the Moon in its orbit using the following measurements to calculate the velocity in its orbit:

The Moon’s distance from the Earth: (calculated using parallax method) about 60 Earth radii (or 384,400 km).

Parallax MethodThe parallax method determines the Moon’s distance by observing its apparent shift against background stars from two distant points on Earth. This angular difference, called the parallax angle (p), relates to the distance(\(D\)) by:

\[ D=\frac{R_E}{\sin{p}} \]

Where \(R_E\) is the radius of the Earth (see below).

Determination of Earth’s RadiusThe Earth’s radius was first scientifically estimated by Eratosthenes (~240 BCE), who used the difference in the Sun’s angle between Syene and Alexandria at noon on the summer solstice. By measuring this angular difference (~7.2°) and knowing the distance between the two cities, he calculated Earth’s circumference to be about 40,000 km, yielding a radius of approximately 6,370 km.

By Newton’s time, more precise measurements came from land-based triangulation. In the 1670s, Jean Picard used observations of a meridian arc near Paris to estimate Earth’s radius as 6,328 km, which Newton used in his gravitational calculations.

And its orbital period was around 27.3 days.

And he found:

\[\frac{a_E}{a_M}\approx \left(\frac{r_M}{r_E}\right)^2 \] where \(a_E\) is the acceleration of an object on Earth, \(a_M\) the acceleration of the moon due to Earth, \(r_M\) the distance of the Moon from the center of the Earth and \(r_E\) the radius of Earth which is distance of the object on Earth from the center of the Earth. This confirmed that the same law governed both falling of objects near Earth as well as orbiting moons.